Submitted by Charles Hugh-Smith of OfTwoMinds blog,

Geography charts the financial destiny of households, at least in terms of housing.

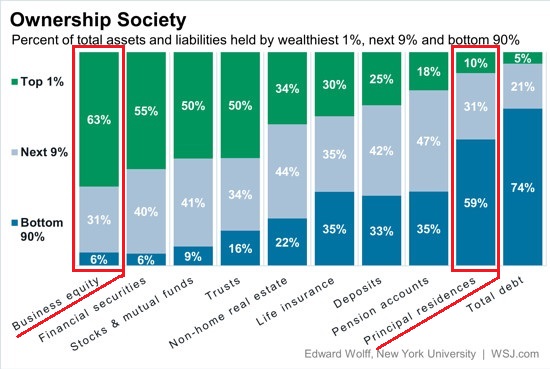

Everyone who follows the statistics of rising income and wealth inequality knows we're becoming a nation of haves and have-nots. What's not being discussed is the role of housing.

Let's start by recalling that for the vast majority of bottom-95% American households, the primary asset is the family home. (The wealthy, not coincidentally, own businesses and income-producing assets.)

Back in 2000, many homes around the U.S. could be purchased for $93,000. It was a substantial sum, but at 2.2 times median household income of $42,128 that year (and less than 2X median family income), it was affordable. (source: U.S. Census Bureau Income Data for 2000)

The conventional down payment (20% of the price) of roughly $19,000 was substantial, but within grasp of a two-income household that lived below their means and scrimped and saved for a few years.

According to the BLS inflation calculator, if the $93,000 home had kept pace with inflation, it would now be worth $128,600 in 2016. Since median household income is now $57,263, the $128,600 home is 2.24 times median household income–in the same ballpark as valuations in 2000. (source: March 2016 median household income via Doug Short)

Guess what a nothing-special sold in 2000 for $93,000 home in a nothing-special S.F. Bay Area neighborhood just sold for. Hint: guess high. How about triple the inflation-adjusted value of $128,000 or $384,000– 4 times the original purchase price of $93,000.

Not even close. The house just sold for $897,000, almost 10 times the 2000 valuation. This is not 2 times median household income; it's 15 times median household income. The conventional down payment of $180,000 is beyond the reach of any household that didn't inherit substantial wealth or get the down payment from wealthy parents.

The down payment of $180,000 exceeds the total wealth of most households.

As for saving up $180,000 for the down payment–only households in the top 5% can even hope to save such a sum after many years of scrimping and saving.

Compare the family wealth of a household that bought a house for $93,000 in 2000 and finds it's now worth $130,000, and the household that finds their home is now worth $900,000. After fifteen years of paying the mortgage and inflation-matching appreciation, the first family may have home equity of around $50,000 to $55,000–a nice sum to help fund retirement, but not enough to insure there will be equity to distribute to heirs once the owners have passed on.

The second household has seen its $19,000 down payment and modest mortgage payments balloon into a cash-out valuation in excess of $850,000. This equity is large enough to not only help fund a comfortable retirement; it's enough to fund cash purchases of homes in lower-cost regions for several offspring.

Imagine the leg-up offered to the children of the second household when their parents' housing windfall enables them to buy a home for cash. If the $850,000 equity was wisely husbanded, it could fund two home purchases (in lower cost areas) and the college expenses of a few grandchildren.

The second household has the advantages of unearned wealth simply from buying a home in a housing bubble area. The children of the first household won't be able to buy a house for cash from the equity of their parents' home–assuming there is any equity left after the parents' retirement expenses are paid.

The offspring of this family will have to save up a down payment (or qualify for a subsidized mortgage), even if they do inherit some percentage of their parents' home equity. They will have to make 30 years of mortgage payments to own their home free and clear.

They may well remain renters for life if they choose to live in high-demand, high-valuation regions such as the S.F. Bay Area or NYC.

The second household's offspring could live mortgage-free, and have a nest egg to invest in their children. Again, this requires wise management of the $850,000 equity, but the generational wealth that could be transferred (if it isn't squandered) will widen the already large gap between the prospects of the two households.

Of course bubblicious valuations will likely decline, but even a 50% drop would still leave the second household with a $450,000 home and a mortgage well under $50,000. Even if this family holds onto the house and never sells it, the equity is available via home-equity lines of credit (HELOCs) or second mortgages.

Geography charts the financial destiny of households, at least in terms of housing. Hot housing markets (San Francisco Bay Area, West Los Angeles, Brooklyn, etc.) were once affordable to everyday middle-class households. Now they are only affordable to wealthy foreigners bringing bucketloads of cash or to the top slice of upper-income households, i.e. those with incomes in excess of $200,000 or more annually.

Those who bought homes in these areas when they were still affordable (the year 2000 or earlier) are reaping gains in wealth that remain unimaginable and unattainable to middle-class households outside these rarified high-demand housing markets.

Housing is yet another driver of our increasingly have/have-not economy.

The post A Nation Of Housing ‘Haves’ & ‘Have-Nots’ appeared first on crude-oil.top.