Submitted by Charles Huigh-Smith of OfTwoMinds blog,

Cheap imports, offshoring of production and the global expansion of financial markets have driven U.S. corporate and financial profits to unprecedented heights.

Globalization (a.k.a. "free" trade) has become an election issue for two reasons: many voters blame "free" trade with China and other nations for job losses in the U.S. and rising income inequality as globalization's "winners" in the U.S. outpace its far more numerous "losers."

A recent article in the New York Times looks at the issue from the perspective of recent economic studies: On Trade, Angry Voters Have a Point (via Lew G.)

The case for globalization based on the fact that it helps expand the economic pie by 3 percent becomes much weaker when it also changes the distribution of the slices by 50 percent.

Before we dig into this complicated set of interconnected macro-dynamics, let's stipulate that there is no such thing as "free" trade. Every trade agreement defines winners and losers by the very design of the agreement.

Also, other issues that are outside the confines of the actual trade agreement can have outsized influence on trade's winners and losers.

For example, trade between the U.S. and China cannot possibly be "free" because China pegs its currency to the U.S. dollar (USD). This peg enables China to arbitrarily keep its products cheaper than they might be if the market set the value of China's yuan.

We must also keep in mind that the owner of the reserve currency, the U.S., must export its currency in size, i.e. run a permanent and substantial trade deficit. I've explained Triffin's Paradox many times; please read (or re-read) these essays if you want to understand why trade deficits are integral to the reserve currency and are not a feature of any particular trade agreement:

Understanding the "Exorbitant Privilege" of the U.S. Dollar (November 19, 2012)

The Federal Reserve, Interest Rates and Triffin's Paradox (November 19, 2015)

Many overlook the fact that central bank interventions play an enormous role in establishing globalization's winners and losers. By lowering interest rates to zero (or less than zero) and flooding the banking sector with credit/liquidity, central banks encouraged an explosion of global carry trades, in which financiers borrow cheap in one currency to buy high-yielding assets in another currency/nation.

The central-bank fueled explosion in credit also threw gasoline on speculative investments in emerging market nations, distorting currencies, markets and trade. The point here is that globalization, financialization and central bank interventions are tightly bound together. We cannot talk about any of these drivers in isolation; together, they form one system we loosely call "global trade."

Let's move on to globalization's impact on jobs, income and income disparity. The article linked above notes that one study found trade with China erased 2.4 million jobs in the U.S. Other studies have found an offsetting consequence: the purchasing power of middle-class and working class households rose by 26% due to globalization's relentless reductions in the cost of imported goods.

We must take all such estimates with a grain of salt, as there are many dynamics in play. The U.S. economy has been roiled by deep structural changes since the late 1960s; there has been no let-up in systemic turbulence: the end of the Bretton Woods stability in foreign exchange markets; the rise of Japanese and Asian imports in the 1970s and 80s; oil shocks and stagflation in the 1970s; the cost of dealing with industrial pollution of our air, water and soil; the tech boom–the cost of processors and memory have fallen while advances in software and robotics accelerate; the explosive changes wrought by the Internet; the rise of China and the Asian Tigers as the world's low-cost workshop, and various speculative debt/fraud bubbles that burst with catastrophic consequences for participants and non-players alike.

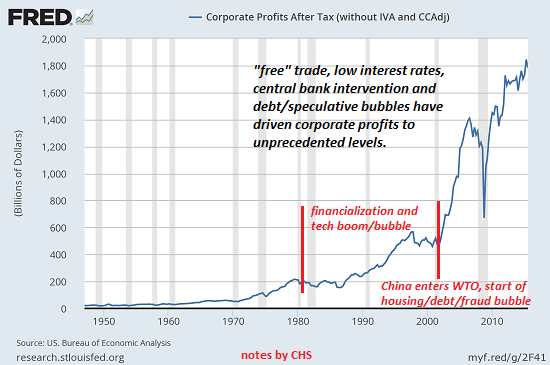

At the risk of overloading you with data, let's look at a few key charts and mark the rise of China's influence, the rise of financialization and income inequality and the explosive rise in U.S. corporate profits.

Here are the charts we'll be reviewing:

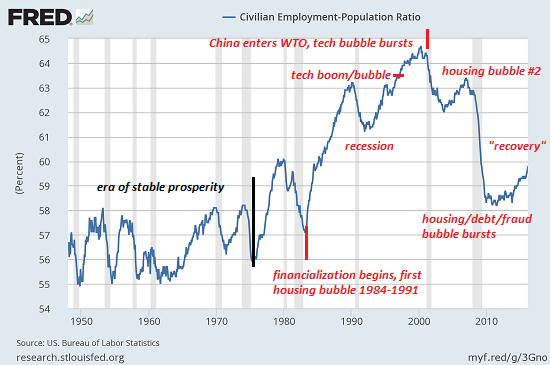

— Civilian employment-population ratio (the percentage of the population who are employed in some fashion, including self-employed and part-time)

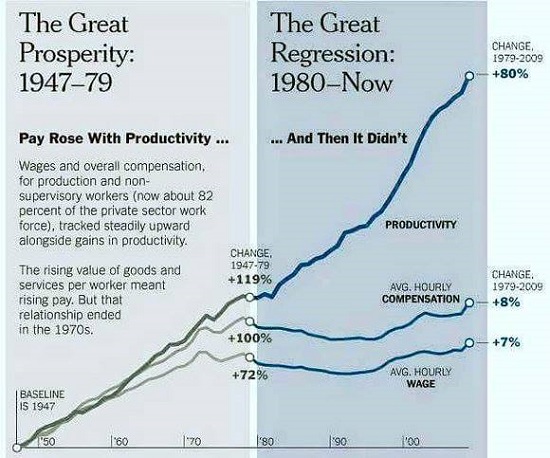

— Productivity (and income disparity)

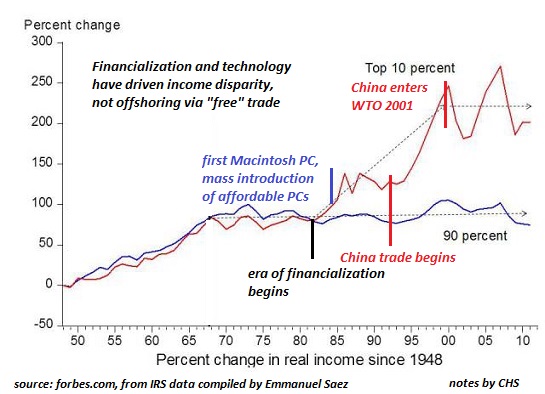

— Income inequality

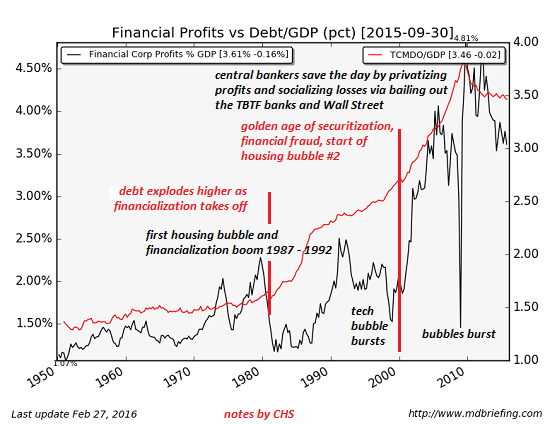

— U.S. Financial profits

— U.S. Corporate profits

On the face of it, the U.S. experienced a multi-decade boom in employment from the early 1980s to 2008. Many have noted that the key demographic driver of this rise in employment was the mass entry of women into the work force. Many believe the loss of purchasing power in the stagflationary 1970s pushed women into the work force as the only means of maintaining household buying power. There were other drivers, of course; nothing this structural reduces down to one single cause.

This chart looks like a giant head-and-shoulders pattern that correlates with the rise and fall of financialization, which is the commodification of previously safe assets such as housing and the explosive rise in debt, derivatives and financial gaming (which quickly morphs into fraud if regulatory agencies fall asleep at the wheel).

It's difficult to separate China's rise and the bursting of the tech bubble, as both occurred in the same time frame; undoubtedly both negatively impacted employment.

The disconnect between productivity and wages really took off with the rise of financialization and cheap technology tools in the early 1980s. This is not coincidental, and can't be pinned on globalization or trade with China, which occurred much later.

As we see in this chart of income inequality, the top 10% (the "winners" in financialization and tech) had already pulled away from the bottom 90% when China entered the WTO in 2001. Clearly, the disparity began before China's trade was large enough to impact the U.S. economy; the dramatic increase in trade with China post-2001 had little impact on the disparity between the top 10% and the bottom 90%.

This chart of financial profits and debt/GDP shows the dramatic expansion of debt from the early 1980s and the explosive rise in financial profits as interest rates were pushed to zero and the debt/housing bubble #2 took off.

Could globalization have been a factor in this monumental expansion of financial profits? As noted above, it's clear that the globalization of finance–carry trades, the expansion of financial markets in emerging nations–gave U.S. financiers, corporations and banks an enormously expanded field for skimming fees and profits via debt, derivatives and speculation.

Total U.S. corporate profits soared once trade with China and the financial free-for-all of housing/debt/fraud took off. This chart makes it clear that the winners from 2001 on were financiers and corporations exploiting two dynamics: offshoring production to China and maintaining product costs to reap outsized profits, and borrowing cheap money to expand overseas and skim profits from carry trades.

What do we get if we add these charts up?

1. Offshoring of production jobs to China et al. undoubtedly slashed jobs for the bottom 90%, but these losses were offset (or masked) by the rise of housing/debt/fraud bubbles that boosted employment in the FIRE sector (finance, insurance, real estate).

2. Financialization and central bank intervention greatly rewarded those with the skills and sociopathologies needed to participate in the resulting debt/fraud booms.

3. U.S. corporations reaped the gains from offshoring jobs, and these gains flowed to top management and those who own corporate shares, i.e. the top 5%.

4. The trend of rising income disparity started long before China's trade was significant enough to impact the U.S. economy, and correlates with the rise of financialization and cheaper technology tools.

5. These trends rewarded management, finance and technology expertise, which are concentrated in the top 10% of the work force.

6. Cheap imports, offshoring of production and the global expansion of financial markets have driven U.S. corporate and financial profits to unprecedented heights. Since these profits largely flow to top management, financiers, technocrats and owners of corporate capital–roughly speaking the top 10% or even top 5%–it's no wonder wealth and income disparity is rising: there is no other output possible in the current system.

Slapping fees on imports (which by the way is illegal in treaties such as the WTO) will not solve the larger problems of reduced employment, stagnant wages and rising income inequality. To make a dent in those issues, we'll need to tackle central bank and central-state policies that have pushed finance and speculative churn to supremacy over the productive economy.

Запись “Free” Trade, Jobs, & Income Inequality: It’s Not As Easy As We Might Think впервые появилась crude-oil.top.