Submitted by Nicole Foss via The Automatic Earth blog,

History teaches us that central authorities dislike escape routes, at least for the majority, and are therefore prone to closing them, so that control of a limited money supply can remain in the hands of the very few. In the 1930s, gold was the escape route, so gold was confiscated. As Alan Greenspan wrote in 1966:

In the absence of the gold standard, there is no way to protect savings from confiscation through monetary inflation. There is no safe store of value. If there were, the government would have to make its holding illegal, as was done in the case of gold. If everyone decided, for example, to convert all his bank deposits to silver or copper or any other good, and thereafter declined to accept checks as payment for goods, bank deposits would lose their purchasing power and government-created bank credit would be worthless as a claim on goods.

The existence of escape routes for capital preservation undermines the viability of the banking system, which is already over-extended, over-leveraged and extremely fragile. This time cash serves that role:

Ironically, though the paper money standard that replaced the gold standard was originally meant to empower governments, it now seems that paper money is perceived as an obstacle to unlimited government power….While paper money isn’t as big impediment to government power as the gold standard was, it is nevertheless an impediment compared to a society with only electronic money. Because of this, the more ardent statists favor the abolition of paper money and a monetary system with only electronic money and electronic payments.

We can therefore expect cash to be increasingly disparaged in order to justify its intended elimination:

Every day, a situation that requires the use of physical cash, feels more and more like an anachronism. It’s like having to listen to music on a CD. John Maynard Keynes famously referred to gold (well, the gold standard specifically) as a “barbarous relic.” Well the new barbarous relic is physical cash. Like gold, cash is physical money. Like gold, cash is still fetishized. And like gold, cash is a costly drain on the economy. A study done at Tufts in 2013 estimated that cash costs the economy $200 billion. Their study included the nugget that consumers spend, on average, 28 minutes per month just traveling to the point where they obtain cash (ATM, etc.). But this is just first-order problem with cash. The real problem, which economists are starting to recognize, is that paper cash is an impediment to effective monetary policy, and therefore economic growth.

Holding cash is not risk free, but cash is nevertheless king in a period of deflation:

Conventional wisdom is that interest rates earned on investments are never less than zero because investors could alternatively hold currency. Yet currency is not costless to hold: It is subject to theft and physical destruction, is expensive to safeguard in large amounts, is difficult to use for large and remote transactions, and, in large quantities, may be monitored by governments.

The acknowledged risks of holding cash are understood and can be managed personally, whereas the substantial risk associated with a systemic banking crisis are entirely outside the control of ordinary depositors. The bank bail-in (rescuing the bank with the depositors’ funds) in Cyprus in early 2013 was a warning sign, to those who were paying attention, that holding money in a bank is not necessarily safe. The capital controls put in place in other locations, for instance Greece, also underline that cash in a bank may not be accessible when needed.

The majority of the developed world either already has, or is introducing, legislation to require depositor bail-ins in the event of bank failures, rather than taxpayer bailouts, in preparation for many more Cyprus-type events, but on a very much larger scale. People are waking up to the fact that a bank balance is not considered their money, but is actually an unsecured loan to the bank, which the bank may or may not repay, depending on its own circumstances.:

Your checking account balance is denominated in dollars, but it does not consist of actual dollars. It represents a promise by a private company (your bank) to pay dollars upon demand. If you write a check, your bank may or may not be able to honor that promise. The poor souls who kept their euros in the form of large balances in Cyprus banks have just learned this lesson the hard way. If they had been holding their euros in the form of currency, they would have not lost their wealth.

Even in relatively untroubled countries, like the UK, it is becoming more difficult to access physical cash in a bank account or to use it for larger purchases. Notice of intent to withdraw may be required, and withdrawal limits may be imposed ‘for your own protection’. Reasons for the withdrawal may be required, ostensibly to combat money laundering and the black economy:

It’s one thing to be required by law to ask bank customers or parties in a cash transaction to explain where their money came from; it’s quite another to ask them how they intend to use the money they wish to withdraw from their own bank accounts. As one Mr Cotton, a HSBC customer, complained to the BBC’s Money Box programme: “I’ve been banking in that bank for 28 years. They all know me in there. You shouldn’t have to explain to your bank why you want that money. It’s not theirs, it’s yours.”

In France, in the aftermath of terrorist attacks there, several anti-cash measures were passed, restricting the use of cash once obtained:

French Finance Minister Michel Sapin brazenly stated that it was necessary to “fight against the use of cash and anonymity in the French economy.” He then announced extreme and despotic measures to further restrict the use of cash by French residents and to spy on and pry into their financial affairs.

These measures…..include prohibiting French residents from making cash payments of more than 1,000 euros, down from the current limit of 3,000 euros….The threshold below which a French resident is free to convert euros into other currencies without having to show an identity card will be slashed from the current level of 8,000 euros to 1,000 euros. In addition any cash deposit or withdrawal of more than 10,000 euros during a single month will be reported to the French anti-fraud and money laundering agency Tracfin.

Tourists in France may also be caught in the net:

France passed another new Draconian law; from the summer of 2015, it will now impose cash requirements dramatically trying to eliminate cash by force. French citizens and tourists will only be allowed a limited amount of physical money. They have financial police searching people on trains just passing through France to see if they are transporting cash, which they will now seize.

This is essentially the Shock Doctrine in action. Central authorities rarely pass up an opportunity to use a crisis to add to their repertoire of repressive laws and practices.

However, even without a specific crisis to draw on as a justification, many other countries have also restricted the use of cash for purchases:

One way they are waging the War on Cash is to lower the threshold at which reporting a cash transaction is mandatory or at which paying in cash is simply illegal. In just the last few years.

- Italy made cash transactions over €1,000 illegal;

- Switzerland has proposed banning cash payments in excess of 100,000 francs;

- Russia banned cash transactions over $10,000;

- Spain banned cash transactions over €2,500;

- Mexico made cash payments of more than 200,000 pesos illegal;

- Uruguay banned cash transactions over $5,000

Other restrictions on the use of cash can be more subtle, but can have far-reaching effects, especially if the ideas catch on and are widely applied:

The State of Louisiana banned “secondhand dealers” from making more than one cash transaction per week. The term has a broad definition and includes Goodwill stores, specialty stores that sell collectibles like baseball cards, flea markets, garage sales and so on. Anyone deemed a “secondhand dealer” is forbidden to accept cash as payment. They are allowed to take only electronic means of payment or a check, and they must collect the name and other information about each customer and send it to the local police department electronically every day.

The increasing application of de facto capital controls, when combined with the prevailing low interest rates, already convince many to hold cash. The possibility of negative rates would greatly increase the likelihood. We are already in an environment of rapidly declining trust, and limited access to what we still perceive as our own funds only accelerates the process in a self-reinforcing feedback loop. More withdrawals lead to more controls, which increase fear and decrease trust, which leads to more withdrawals. This obviously undermines the perceived power of monetary policy to stimulate the economy, hence the escape route is already quietly closing.

In a deflationary spiral, where the money supply is crashing, very little money is in circulation and prices are consequently falling almost across the board, possessing purchasing power provides for the freedom to pursue opportunities as they present themselves, and to avoid being backed into a corner. The purchasing power of cash increases during deflation, even as electronic purchasing power evaporates. Hence cash represents freedom of action at a time when that will be the rarest of ‘commodities’.

Governments greatly dislike cash, and increasingly treat its use, or the desire to hold it, especially in large denominations, with great suspicion:

Why would a central bank want to eliminate cash? For the same reason as you want to flatten interest rates to zero: to force people to spend or invest their money in the risky activities that revive growth, rather than hoarding it in the safest place. Calls for the eradication of cash have been bolstered by evidence that high-value notes play a major role in crime, terrorism and tax evasion. In a study for the Harvard Business School last week, former bank boss Peter Sands called for global elimination of the high-value note.

Britain’s “monkey” — the £50 — is low-value compared with its foreign-currency equivalents, and constitutes a small proportion of the cash in circulation. By contrast, Japan’s ¥10,000 note (worth roughly £60) makes up a startling 92% of all cash in circulation; the Swiss 1,000-franc note (worth around £700) likewise. Sands wants an end to these notes plus the $100 bill, and the €500 note – known in underworld circles as the “Bin Laden”.

Cash is largely anonymous, untraceable and uncontrollable, hence it makes central authorities, in a system increasingly requiring total buy-in in order to function, extremely uncomfortable. They regard there being no legitimate reason to own more than a small amount of it in physical form, as its ownership or use raises the spectre of tax evasion or other illegal activities:

The insidious nature of the war on cash derives not just from the hurdles governments place in the way of those who use cash, but also from the aura of suspicion that has begun to pervade private cash transactions. In a normal market economy, businesses would welcome taking cash. After all, what business would willingly turn down customers? But in the war on cash that has developed in the thirty years since money laundering was declared a federal crime, businesses have had to walk a fine line between serving customers and serving the government. And since only one of those two parties has the power to shut down a business and throw business owners and employees into prison, guess whose wishes the business owner is going to follow more often?

The assumption on the part of government today is that possession of large amounts of cash is indicative of involvement in illegal activity. If you’re traveling with thousands of dollars in cash and get pulled over by the police, don’t be surprised when your money gets seized as “suspicious.” And if you want your money back, prepare to get into a long, drawn-out court case requiring you to prove that you came by that money legitimately, just because the courts have decided that carrying or using large amounts of cash is reasonable suspicion that you are engaging in illegal activity….

….Centuries-old legal protections have been turned on their head in the war on cash. Guilt is assumed, while the victims of the government’s depredations have to prove their innocence….Those fortunate enough to keep their cash away from the prying hands of government officials find it increasingly difficult to use for both business and personal purposes, as wads of cash always arouse suspicion of drug dealing or other black market activity. And so cash continues to be marginalized and pushed to the fringes.

Despite the supposed connection between crime and the holding of physical cash, the places where people are most inclined (and able) to store cash do not conform to the stereotype at all:

Are Japan and Switzerland havens for terrorists and drug lords? High-denomination bills are in high demand in both places, a trend that some politicians claim is a sign of nefarious behavior. Yet the two countries boast some of the lowest crime rates in the world. The cash hoarders are ordinary citizens responding rationally to monetary policy. The Swiss National Bank introduced negative interest rates in December 2014. The aim was to drive money out of banks and into the economy, but that only works to the extent that savers find attractive places to spend or invest their money. With economic growth an anemic 1%, many Swiss withdrew cash from the bank and stashed it at home or in safe-deposit boxes. High-denomination notes are naturally preferred for this purpose, so circulation of 1,000-franc notes (worth about $1,010) rose 17% last year. They now account for 60% of all bills in circulation and are worth almost as much as Serbia’s GDP.

Japan, where banks pay infinitesimally low interest on deposits, is a similar story. Demand for the highest-denomination ¥10,000 notes rose 6.2% last year, the largest jump since 2002. But 10,000 Yen notes are worth only about $88, so hiding places fill up fast. That explains why Japanese went on a safe-buying spree last month after the Bank of Japan announced negative interest rates on some reserves. Stores reported that sales of safes rose as much as 250%, and shares of safe-maker Secom spiked 5.3% in one week.

In Germany too, negative interest rates are considered intolerable, banks are increasingly being seen as risky prospects, and physical cash under one’s own control is coming to be seen as an essential part of a forward-thinking financial strategy:

First it was the news that Raiffeisen Gmund am Tegernsee, a German cooperative savings bank in the Bavarian village of Gmund am Tegernsee, with a population 5,767, finally gave in to the ECB’s monetary repression, and announced it’ll start charging retail customers to hold their cash. Then, just last week, Deutsche Bank’s CEO came about as close to shouting fire in a crowded negative rate theater, when, in a Handelsblatt Op-Ed, he warned of “fatal consequences” for savers in Germany and Europe — to be sure, being the CEO of the world’s most systemically risky bank did not help his cause.

That was the last straw, and having been patient long enough, the German public has started to move. According to the WSJ, German savers are leaving the “security of savings banks” for what many now consider an even safer place to park their cash: home safes. We wondered how many “fatal” warnings from the CEO of DB it would take, before this shift would finally take place. As it turns out, one was enough….

….“It doesn’t pay to keep money in the bank, and on top of that you’re being taxed on it,” said Uwe Wiese, an 82-year-old pensioner who recently bought a home safe to stash roughly €53,000 ($59,344), including part of his company pension that he took as a payout. Burg-Waechter KG, Germany’s biggest safe manufacturer, posted a 25% jump in sales of home safes in the first half of this year compared with the year earlier, said sales chief Dietmar Schake, citing “significantly higher demand for safes by private individuals, mainly in Germany.”….

….Unlike their more “hip” Scandinavian peers, roughly 80% of German retail transactions are in cash, almost double the 46% rate of cash use in the U.S., according to a 2014 Bundesbank survey….Germany’s love of cash is driven largely by its anonymity. One legacy of the Nazis and East Germany’s Stasi secret police is a fear of government snooping, and many Germans are spooked by proposals of banning cash transactions that exceed €5,000. Many Germans think the ECB’s plan to phase out the €500 bill is only the beginning of getting rid of cash altogether. And they are absolutely right; we can only wish more Americans showed the same foresight as the ordinary German….

….Until that moment, however, as a final reminder, in a fractional reserve banking system, only the first ten or so percent of those who “run” to the bank to obtain possession of their physical cash and park it in the safe will succeed. Everyone else, our condolences.

The internal stresses are building rapidly, stretching economy after economy to breaking point and prompting aware individuals to protect themselves proactively:

People react to these uncertainties by trying to protect themselves with cash and guns, and governments respond by trying to limit citizens’ ability to do so.

If this play has a third act, it will involve the abolition of cash in some major countries, the rise of various kinds of black markets (silver coins, private-label cash, cryptocurrencies like bitcoin) that bypass traditional banking systems, and a surge in civil unrest, as all those guns are put to use.

The speed with which cash, safes and guns are being accumulated — and the simultaneous intensification of the war on cash — imply that the stress is building rapidly, and that the third act may be coming soon.

Despite growing acceptance of electronic payment systems, getting rid of cash altogether is likely to be very challenging, particularly as the fear and state of financial crisis that drives people into cash hoarding is very close to reasserting itself. Cash has a very long history, and enjoys greater trust than other abstract means for denominating value. It is likely to prove tenacious, and unable to be eliminated peacefully. That is not to suggest central authorities will not try. At the heart of financial crisis lies the problem of excess claims to underlying real wealth. The bursting of the global bubble will eliminate the vast majority of these, as the value of credit instruments, hitherto considered to be as good as money, will plummet on the realisation that nowhere near all financial promises made can possibly be kept.

Cash would then represent the a very much larger percentage of the remaining claims to limited actual resources — perhaps still in excess of the available resources and therefore subject to haircuts. Not only the quantity of outstanding cash, but also its distribution, may not be to central authorities liking. There are analogous precedents for altering legal currency in order to dispossess ordinary people trying to protect their stores of value, depriving them of the benefit of their foresight. During the Russian financial crisis of 1998, cash was not eliminated in favour of an electronic alternative, but the currency was reissued, which had a similar effect. People were required to convert their life savings (often held ‘under the mattress’) from the old currency to the new. This was then made very difficult, if not impossible, for ordinary people, and many lost the entirety of their life savings as a result.

A Cashless Society?

The greater the public’s desire to hold cash to protect themselves, the greater will be the incentive for central banks and governments to restrict its availability, reduce its value or perhaps eliminate it altogether in favour of electronic-only payment systems. In addition to commercial banks already complicating the process of making withdrawals, central banks are actively considering, as a first step, mechanisms to impose negative interest rates on physical cash, so as to make the escape route appear less attractive:

Last September, the Bank of England’s chief economist, Andy Haldane, openly pondered ways of imposing negative interest rates on cash — ie shrinking its value automatically. You could invalidate random banknotes, using their serial numbers. There are £63bn worth of notes in circulation in the UK: if you wanted to lop 1% off that, you could simply cancel half of all fivers without warning. A second solution would be to establish an exchange rate between paper money and the digital money in our bank accounts. A fiver deposited at the bank might buy you a £4.95 credit in your account.

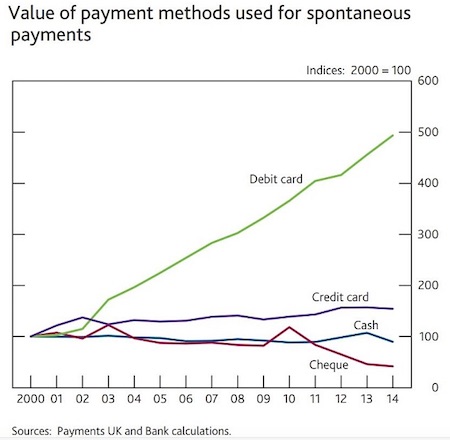

To put it mildly, invalidating random banknotes would be highly likely to result in significant social blowback, and to accelerate the evaporation of trust in governing authorities of all kinds. It would be far more likely for financial authorities to move toward making official electronic money the standard by which all else is measured. People are already used to using electronic money in the form of credit and debit cards and mobile phone money transfers:

I can remember the moment I realised the era of cash could soon be over. It was Australia Day on Bondi Beach in 2014. In a busy liquor store, a man wearing only swimming shorts, carrying only a mobile phone and a plastic card, was delaying other people’s transactions while he moved 50 Australian dollars into his current account on his phone so that he could buy beer. The 30-odd youngsters in the queue behind him barely murmured; they’d all been in the same predicament. I doubt there was a banknote or coin between them….The possibility of a cashless society has come at us with a rush: contactless payment is so new that the little ping the machine makes can still feel magical. But in some shops, especially those that cater for the young, a customer reaching for a banknote already produces an automatic frown. Among central bankers, that frown has become a scowl.

In some states almost anything, no matter how small, can be purchased electronically. Everything down to, and including, a cup of coffee from a roadside stall can be purchased in New Zealand with an EFTPOS (debit) card, hence relatively few people carry cash. In Scandinavian countries, there are typically more electronic payment options than cash options:

Sweden became the first country to enlist its own citizens as largely willing guinea pigs in a dystopian economic experiment: negative interest rates in a cashless society. As Credit Suisse reports, no matter where you go or what you want to purchase, you will find a small ubiquitous sign saying “Vi hanterar ej kontanter” (“We don’t accept cash”)….A similar situation is unfolding in Denmark, where nearly 40% of the paying demographic use MobilePay, a Danske Bank app that allows all payments to be completed via smartphone.

Even street vendors selling “Situation Stockholm”, the local version of the UK’s “Big Issue” are also able to take payments by debit or credit card.

Ironically, cashlessness is also becoming entrenched in some African countries. One might think that electronic payments would not be possible in poor and unstable subsistence societies, but mobile phones are actually very common in such places, and means for electronic payments are rapidly becoming the norm:

While Sweden and Denmark may be the two nations that are closest to banning cash outright, the most important testing ground for cashless economics is half a world away, in sub-Saharan Africa. In many African countries, going cashless is not merely a matter of basic convenience (as it is in Scandinavia); it is a matter of basic survival. Less than 30% of the population have bank accounts, and even fewer have credit cards. But almost everyone has a mobile phone. Now, thanks to the massive surge in uptake of mobile communications as well as the huge numbers of unbanked citizens, Africa has become the perfect place for the world’s biggest social experiment with cashless living.

Western NGOs and GOs (Government Organizations) are working hand-in-hand with banks, telecom companies and local authorities to replace cash with mobile money alternatives. The organizations involved include Citi Group, Mastercard, VISA, Vodafone, USAID, and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

In Kenya the funds transferred by the biggest mobile money operator, M-Pesa (a division of Vodafone), account for more than 25% of the country’s GDP. In Africa’s most populous nation, Nigeria, the government launched a Mastercard-branded biometric national ID card, which also doubles up as a payment card. The “service” provides Mastercard with direct access to over 170 million potential customers, not to mention all their personal and biometric data. The company also recently won a government contract to design the Huduma Card, which will be used for paying State services. For Mastercard these partnerships with government are essential for achieving its lofty vision of creating a “world beyond cash.”

Countries where electronic payment is already the norm would be expected to be among the first places to experiment with a fully cashless society as the transition would be relatively painless (at least initially). In Norway two major banks no longer issue cash from branch offices, and recently the largest bank, DNB, publicly called for the abolition of cash. In rich countries, the advent of a cashless society could be spun in the media in such a way as to appear progressive, innovative, convenient and advantageous to ordinary people. In poor countries, people would have no choice in any case.

Testing and developing the methods in societies with no alternatives and then tantalizing the inhabitants of richer countries with more of the convenience to which they have become addicted is the clear path towards extending the reach of electronic payment systems and the much greater financial control over individuals that they offer:

Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, in its 2015 annual letter, adds a new twist. The technologies are all in place; it’s just a question of getting us to use them so we can all benefit from a crimeless, privacy-free world. What better place to conduct a massive social experiment than sub-Saharan Africa, where NGOs and GOs (Government Organizations) are working hand-in-hand with banks and telecom companies to replace cash with mobile money alternatives? So the annual letter explains: “(B)ecause there is strong demand for banking among the poor, and because the poor can in fact be a profitable customer base, entrepreneurs in developing countries are doing exciting work – some of which will “trickle up” to developed countries over time.”

What the Foundation doesn’t mention is that it is heavily invested in many of Africa’s mobile-money initiatives and in 2010 teamed up with the World Bank to “improve financial data collection” among Africa’s poor. One also wonders whether Microsoft might one day benefit from the Foundation’s front-line role in mobile money….As a result of technological advances and generational priorities, cash’s days may well be numbered. But there is a whole world of difference between a natural death and euthanasia. It is now clear that an extremely powerful, albeit loose, alliance of governments, banks, central banks, start-ups, large corporations, and NGOs are determined to pull the plug on cash — not for our benefit, but for theirs.

Whatever the superficially attractive media spin, joint initiatives like the Better Than Cash Alliance serve their founders, not the public. This should not come as a surprise, but it probably will as we sleepwalk into giving up very important freedoms:

As I warned in We Are Sleepwalking Towards a Cashless Society, we (or at least the vast majority of people in the vast majority of countries) are willing to entrust government and financial institutions — organizations that have already betrayed just about every possible notion of trust — with complete control over our every single daily transaction. And all for the sake of a few minor gains in convenience. The price we pay will be what remains of our individual freedom and privacy.

The post Negative Rates & The War On Cash, Part 2: “Closing The Escape Routes” appeared first on crude-oil.top.