Submitted by David Stockman via Contra Corner blog,

No wonder the Red Ponzi consumed more cement during three years (2011-2013) than did the US during the entire twentieth century. Enabled by an endless $30 trillion flow of credit from its state controlled banking apparatus and its shadow banking affiliates, China went berserk building factories, warehouses, ports, office towers, malls, apartments, roads, airports, train stations, high speed railways, stadiums, monumental public buildings and much more.

If you want an analogy, 6.6 gigatons of cement is 14.5 trillion pounds. The Hoover dam used about 1.8 billion pounds of cement. So in 3 years China consumed enough cement to build the Hoover dam 8,000 times over—-160 of them for every state in the union!

Having spent the last ten days in China, I can well and truly say that the Middle Kingdom is back. But its leitmotif is the very opposite to the splendor of the Forbidden City.

The Middle Kingdom has been reborn in towers of preformed concrete. They rise in their tens of thousands in every direction on the horizon. They are connected with ribbons of highways which are scalloped and molded to wind through the endless forest of concrete verticals. Some of them are occupied. Alot, not.

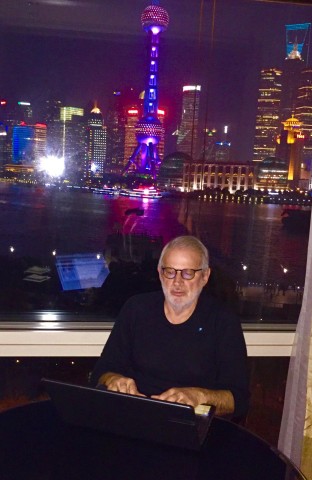

The “before” and “after” contrast of Shanghai’s famous Pudong waterfront is illustrative of the illusion.

The first picture below is from about 1990 at a time before Mr. Deng discovered the printing press in the basement of the People’s Bank of China and proclaimed that it is glorious to be rich; and that if you were 18 and still in full possession of your digital dexterity and visual acuity it was even more glorious to work 12 hours per day 6 days per week in an export factory for 35 cents per hour.

I don’t know if the first picture is accurate as to its exact vintage. But by all accounts the glitzy skyscrapers of today’s Pudong waterfront did ascend during the last 25 years from a rundown, dimly lit area of muddy streets on the east side of Huangpu River. The pictured area was apparently shunned by all except the most destitute of Mao’s proletariat.

But the second picture I can vouch for. It’s from my window at the Peninsula Hotel on the Bund which lies directly accross on the west side of the Huangpu River and was taken as I typed this post.

Today’s Pudong district does look spectacular—–presumably a 21st century rendition of the glory of the Qing, the Ming, the Soong, the Tang and the Han.

But to conclude that would be to be deceived.The apparent prosperity is not that of a sustainable economic miracle; its the front street of the greatest Potemkin Village in world history.

The heart of the matter is that output measured by Keynesian GDP accounting—-especially China’s blatantly massaged variety— isn’t sustainable wealth if it is not rooted in real savings, efficient capital allocation and future productivity growth. Nor does construction and investment which does not earn back its cost of capital over time contribute to the accumulation of real wealth.

Needless to say, China’s construction and “investment” binge manifestly does not meet these criteria in the slightest. It was funded with credit manufactured by state controlled banks and their shadow affiliates, not real savings. It was driven by state initiated growth plans and GDP targets. These were cascaded from the top down to the province, county and local government levels—–an economic process which is the opposite of entrepreneurial at-risk assessments of future market based demand and profits.

China’s own GDP statistics are the smoking gun. During the last 15 years fixed asset investment—–in private business, state companies, households and the “public sector” combined—–has averaged 50% of GDP. That’s per se crazy.

Even in the heyday of its 1960s and 1970s boom, Japan’s fixed asset investment never reached more than 30% of GDP. Moreover, even that was not sustained year in and year out (they had three recessions), and Japan had at least a semblance of market pricing and capital allocation—unlike China’s virtual command and control economy.

The reason that Wall Street analysts and fellow-traveling Keynesian economists miss the latter point entirely is because China’s state-driven economy works through credit allocation rather than by tonnage toting commissars. The gosplan is implemented by the banking system and, increasingly, through China’s mushrooming and metastasizing shadow banking sector. The latter amounts to trillions of credit potted in entities which have sprung up to evade the belated growth controls that the regulators have imposed on the formal banking system.

For example, Beijing tried to cool down the residential real estate boom by requiring 30% down payments on first mortgages and by virtually eliminating mortgage finance on second homes and investment properties. So between 2013 and the present more than 2,500 on-line peer-to-peer lending outfits (P2P) materialized—-mostly funded or sponsored by the banking system—– and these entities have advanced more than $2 trillion of new credit.

The overwhelming share went into meeting “downpayments” and other real estate speculations. On the one hand, that reignited the real estate bubble——especially in the Tier I cities were prices have risen by 20% to 60% during the last year. At the same time, this P2P eruption in the shadow banking system has encouraged the construction of even more excess housing stock in an economy that already has upwards of 70 million empty units.

In short, China has become a credit-driven economic madhouse. The 50% of GDP attributable to fixed asset investment actually constitutes the most spectacular spree of malinvestment and waste in recorded history. It is the footprint of a future depression, not evidence of sustainable growth and prosperity.

Consider a boundary case analogy. With enough fiat credit during the last three years, the US could have built 160 Hoover dams on dry land in each state. That would have elicited one hellacious boom in the jobs market, gravel pits, cement truck assembly plants, pipe and tube mills, architectural and engineering offices etc. The profits and wages from that dam building boom, in turn, would have generated a secondary cascade of even more phony “growth”.

But at some point, the credit expansion would stop. The demand for construction materials, labor, machinery and support services would dry-up; the negative multiplier on incomes, spending and investment would kick-in; and the depression phase of a crack-up boom would exact its drastic revenge.

The fact is, China has been in a crack-up boom for the last two decades, and one which transcends anything that the classic liberal economists ever imagined. Since 1995, credit outstanding has grown from $500 billion to upwards of $30 trillion, and that’s only counting what’s visible. But the very idea of a 60X expansion of credit in hardly two decades in the context of top-down allocation system suffused with phony data and endless bureaucratic corruption defies economic rationality and common sense.

Stated differently, China is not simply a little over-done, and it’s not in some Keynesian transition from exports and investment to domestic services and consumption. Instead, China’s fantastically over-built industry and public infrastructure embodies monumental economic waste equivalent to the construction of pyramids with shovels and spoons and giant dams on dry land.

Accordingly, when the credit pyramid finally collapses or simply stops growing, the pace of construction will decline dramatically, leaving the Red Ponzi riddled with economic air pockets and negative spending multipliers.

Take the simple case of the abandoned cement mixer plant pictured below. The high wages paid in that abandoned plant are now gone; the owners have undoubtedly fled and their high living extravagance is no more. Nor is this factory’s demand still extant for steel sheets and plates, freight services, electric power, waste hauling, equipment replacement parts and on down the food chain.

And, no, a wise autocracy in Beijing will not be able to off-set the giant deflationary forces now assailing the construction and industrial heartland of China’s hothouse economy with massive amounts of new credit to jump start green industries and neighborhood recreation facilities. That’s because China has already shot is its credit wad, meaning that every new surge in its banking system will trigger even more capital outflow and expectations of FX depreciation.

Moreover, any increase in fiscal spending not funded by credit expansion will only rearrange the deck chairs on the titanic. Indeed, whatever borrowing headroom Beijing has left will be needed to fund the bailouts of its banking and credit system. Without massive outlays for the purpose of propping-up and stabilizing China’s vast credit Ponzi, there will be economic and social chaos as the tide of defaults and abandonments swells.

Empty factories like the above—–and China is crawling with them—–are a screaming marker of an economic doomsday machine. They bespeak an inherently unsustainable and unstable simulacrum of capitalism where the purpose of credit has been to fund state mandated GDP quota’s, not finance efficient investments with calculable risks and returns.

The relentless growth of China’s aluminum production is just one more example. When China’s construction and investment binge finally stops, there will be a huge decline in industry wages, profits and supply chain activity.

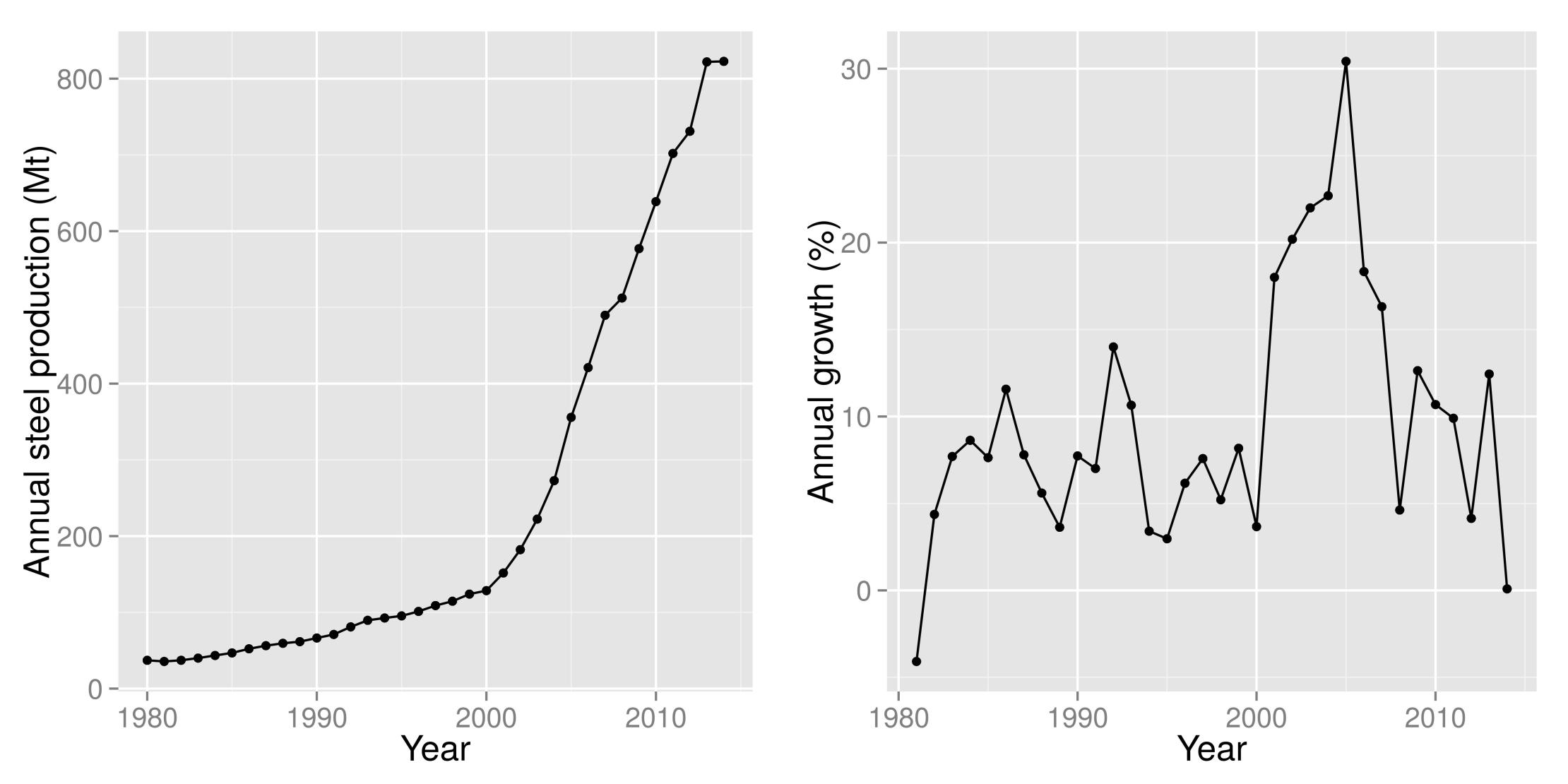

But the mother of all malinvestments sprang up in China’s steel industry. From about 70 million tons of production in the early 1990s, it exploded to 825 million tons in 2014. Beyond that, it is the capacity build-out behind the chart below which tells the full story.

To wit, Beijing’s tsunami of cheap credit enabled China’s state-owned steel companies to build new capacity at an even more fevered pace than the breakneck growth of annual production. Consequently, annual crude steel capacity now stands at nearly 1.4 billion tons, and nearly all of that capacity—-about 70% of the world total—— was built in the last ten years.

Needless to say, it’s a sheer impossibility to expand efficiently the heaviest of heavy industries by 17X in a quarter century.

What happened is that China’s aberrationally massive steel industry expansion created a significant one-time increment of demand for its own products. That is, plate, structural and other steel shapes that go into blast furnaces, BOF works, rolling mills, fabrication plants, iron ore loading and storage facilities, as well as into plate and other steel products for shipyards where new bulk carriers were built and into the massive equipment and infrastructure used at the iron ore mines and ports.

That is to say, the Chinese steel industry has been chasing its own tail, but the merry-go-round has now stopped. For the first time in three decades, steel production in 2015 was down 2-3% from 2014’s peak of 825 million tons and is projected to drop to 750 million tons next year, even by the lights of the China miracle believers.

And that’s where the pyramid building nature of China’s insane steel industry investment comes in. The industry is not remotely capable of “rationalization” in the DM economy historical sense. Even Beijing’s much ballyhooed 100-150 million ton plant closure target is a drop in the bucket—-and its not scheduled to be completed until 2020 anyway.

To wit, China will be lucky to have 400 million tons of true sell-through demand—-that is, on-going domestic demand for sheet steel to go into cars and appliances and for rebar and structural steel to be used in replacement construction once the current one-time building binge finally expires.

For instance, China’s construction and shipbuilding industries consumed about 500 million tons per year at the crest of the building boom. But shipyards are already going radio silent and the end of China’s manic eruption of concrete, rebar and I-beams is not far behind. Use of steel for these purposes could easily drop to 200 million tons on a steady state basis.

Bu contrast, China’s vaunted auto industry uses only 45 million tons of steel per year, and consumer appliances consume less than 12 million tons. In most developed economies autos and white goods demand accounts for about 20% of total steel use.

Likewise, much of the current 200 million tons of steel which goes into machinery and equipment including massive production of mining and construction machines, rails cars etc. is of a one-time nature and could easily drop to 100 million tons on a steady state replacement basis. So its difficult to see how China will ever have recurring demand for even 400 million tons annually, yet that’s just 30% of its massive capacity investment.

In short, we are talking about wholesale abandonment of a half billion tons of steel capacity or more. That is, the destruction of steel industry capacity greater than that of Japan, the EC and the US combined.

Needless to say, that thunderous liquidation will generate a massive loss of labor income and profits and devastating contraction of the steel industry’s massive and lengthy supply chain. And that’s to say nothing of the labor market disorder and social dislocation when China is hit by the equivalent of dozens of burned-out Youngstowns and Pittsburgs.

And it is also evident that it will not be in a position to dump its massive surplus on the rest of the world. Already trade barriers against last year’s 110 million tons of exports are being thrown up in Europe, North America, Japan and nearly everywhere else.

This not only means that China has upwards of a half-billion tons of excess capacity that will crush prices and profits, but, more importantly, that the one-time steel demand for steel industry CapEx is over and done. And that means shipyards and mining equipment, too.

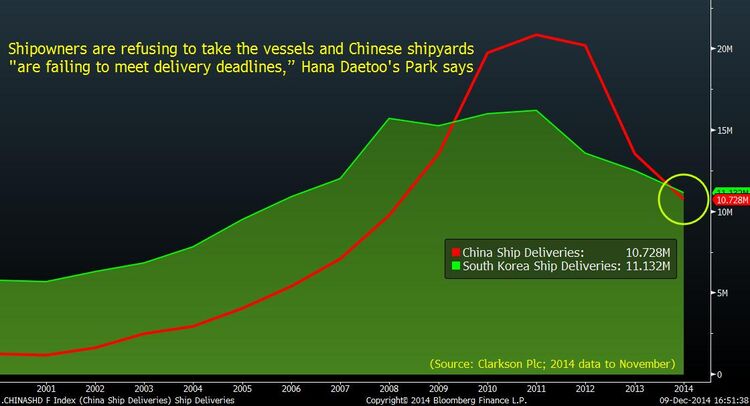

That is already evident in the vanishing order book for China’s giant shipbuilding industry. The latter is focussed almost exclusively on dry bulk carriers——-the very capital item that delivered into China’s vast industrial maw the massive tonnages of iron ore, coking coal and other raw materials. But within in a year or two most of China’s shipyards will be closed as its backlog rapidly vanishes under a crushing surplus of dry bulk capacity that has no precedent, and which has driven the Baltic shipping rate index to historic lows.

Still, we now have the absurdity of China’s state shipping company (Cosco) ordering 11 massive containerships that it can’t possibly need (China’s year-to-date exports are down 20%) in order to keep its vastly overbuilt shipyards in new orders. And those wasteful new orders, in turn will take plate from China’s white elephant steel mills:

This and other state-owned shipyards are being kept busy by China Ocean Shipping Group, better known as Cosco, the country’s largest shipper by carrying capacity, which ordered 11 huge container ships last year. Caixin, the financial magazine, reported that the three ships ordered from Waigaoqiao would be able to carry 20,000 20ft containers, making them the world’s largest.

The weakening yuan and China’s waning appetite for raw materials have come around to bite the country’s shipbuilders, raising the odds that more shipyards will soon be shuttered.

About 140 yards in the world’s second-biggest shipbuilding nation have gone out of business since 2010, and more are expected to close in the next two years after only 69 won orders for vessels last year, JPMorgan Chase & Co. analysts Sokje Lee and Minsung Lee wrote in a Jan. 6 report. That compares with 126 shipyards that fielded orders in 2014 and 147 in 2013.

Total orders at Chinese shipyards tumbled 59 percent in the first 11 months of 2015, according to data released Dec. 15 by the China Association of the National Shipbuilding Industry. Builders have sought government support as excess vessel capacity drives down shipping rates and prompts customers to cancel contracts. Zhoushan Wuzhou Ship Repairing & Building Co. last month became the first state-owned shipbuilder to go bankrupt in a decade.

It is not surprising that China’s massive shipbuilding industry is in distress and that it is attempting to export its troubles to the rest of the world. Yet subsidizing new builds will eventually add more downward pressure to global shipping rates—-rates which are already at all time lows. And as the world’s shipping companies are driven into insolvency, they will take the European banks which have financed them down the drink, as well.

Still, the fact that China is exporting yet another downward deflationary spiral to the world economy is not at all surprising. After all, China’s shipbuilding output rose by 11X in 10 years!

The worst thing is that just as the Red Ponzi is beginning to crack, China’s leader is rolling out the paddy wagons and reestablishing a cult of the leader that more and more resembles nothing so much as a Maoist revival. As Xi said while making the rounds of the state media recently, its job is to:

“……reflect the will of the Party, mirror the views of the Party, preserve the authority of the Party, preserve the unity of the Party and achieve love of the Party, protection of the Party and acting for the Party.”

The above proclamation needs no amplification. China will increasingly plunge into a regime of harsh, capricious dictatorship as the Red Depression unfolds. And that will only fuel the downward spiral which is already gathering momentum.

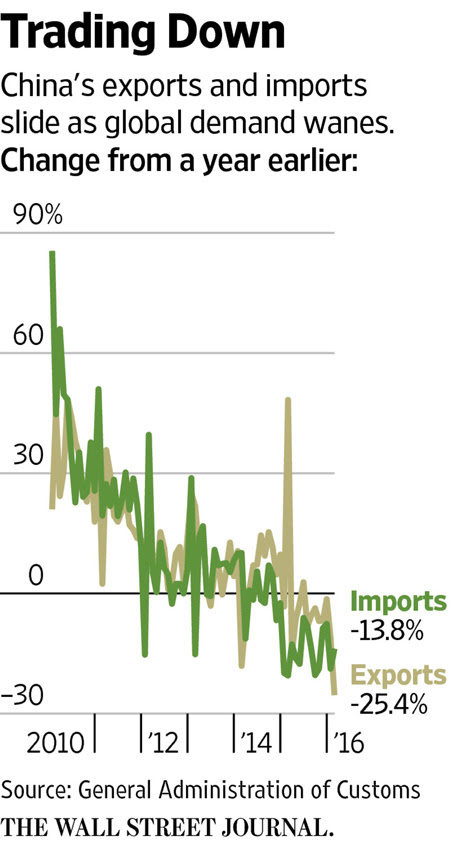

During the first two months of 2016, for example, China export machine has buckled badly. Exports fell 25.4% in February year over year, following an 11.2% decline in January.

Likewise, local economies in its growing rust belt, such as parts of Heilongjiang, in far northeast China have dropped by 20% in the last two years and are still in free fall. Coal prices in those areas have plunged by 65% since 2011 and hundreds of mines have been closed or abandoned.

The picture below is epigrammatic of what lies behind the great Potemkin Village which is the Red Ponzi.

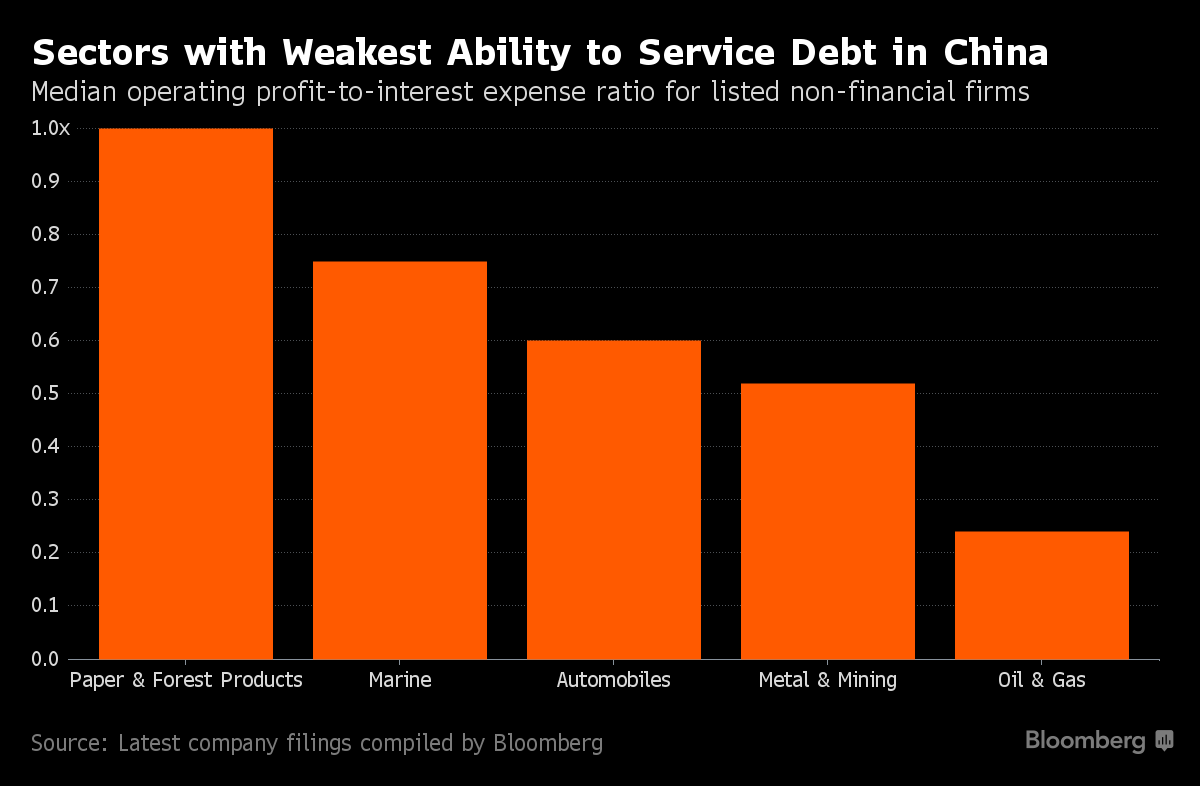

While pictures can often tell a thousand words, as in the above, sooner or later then numbers are no less revealing. The fact is, no economy can undergo the fantastic eruption of credit that has occurred in China during the last two decades without eventually coming face to face with a day of reckoning. And a Bloomberg analysis of the shocking deterioration of credit metrics in the non-financial sector of China suggests that day is coming fast.

To wit, overall interest expense coverage by operating income has plunged dramatically, and virtually every major industrial sector of the Red Ponzi is underwater with a coverage ratio of less than 1.0X.

Stated differently, during the first two months of this year China’s total social financing or credit outstanding surged at an incredible $6 trillion annual rate. That means the Red Ponzi is on track to bury itself in a further debt load equal to 55% of GDP by year end.

But that’s not the half of it. What is evident from the Bloomberg data below is that the overwhelming share of these new borrowings are being allocated to pay interest on existing debt because it is not being covered by current operating profits.

Firms generated just enough operating profit to cover the interest expenses on their debt twice, down from almost six times in 2010, according to data compiled by Bloomberg going back to 1992 from non-financial companies traded in Shanghai and Shenzhen. Oil and gas corporates were the weakest at 0.24 times, followed by the metals and mining sector at 0.52.

The People’s Bank of China has lowered benchmark interest rates six times since 2014, driving a record rally in the bond market and underpinning a jump in debt to 247 percent of gross domestic product. Yet economic growth has slumped to the slowest in a quarter century and profits for the listed companies grew only 3 percent in 2015, down from 11 percent in 2014. The mounting debt burden has caused at least seven firms to miss local bond payments this year, already reaching the tally for the whole of last year.

“We will likely see a wave of bankruptcies and restructurings when the interest coverage ratio drops further,” said Xia Le, chief economist for Asia at Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria SA in Hong Kong. “Return on assets for Chinese companies has been declining due to rising debt. Profitability is also slowing due to overcapacity in many sectors, which has weakened the ability of companies to repay their debts.”

Massive borrowing to pay the interest is everywhere and always a sign that the the end is near. The crack-up phase of China’s insane borrowing and building boom is surely at hand.

The post The New Middle Kingdom Of Concrete And The Red Depression Ahead appeared first on crude-oil.top.