Submitted by Jeffrey Snider via Alhambra Investment Partners,

It’s not just that there was an obvious and intense change in sentiment, as that is quite common among and within markets. It is more so that this repetition is a little too familiar. In January, the mainstream was taken aback as the world looked headed for a very dark place, all “unexpected” of course. Just a few months later, it has been nothing but a huge sigh of relief as if anyone might know for sure the danger has passed.

It has been nearly universal. In Canada, for example, as a proxy for both US and Chinese economies, this exhale into renewed optimism was a big one:

“External developments have conspired against Canada’s economy so far this year, as soft U.S. demand to start 2015 delivered a powerful blow to an economy already reeling from the sharp decline in oil prices,” TD said.

But “the worst is likely behind us.”

In emerging markets, the “flows” have been intense on the same exact premise (and wording).

“People are saying the worst is behind us so it’s no surprise funds are flowing back in. As June approaches there will be more volatility but for now and at least into the early part of May there will still be some inflows.”

Even in the US, as reported today, the economic concerns that were ubiquitous to start the year have softened into almost forgotten memories.

“Recent claims of the demise of the U.S. consumer have been greatly exaggerated,” said Capital Economics economist Steve Murphy. Economists surveyed by The Wall Street Journal had expected April sales would be increase 0.8% from the prior month.

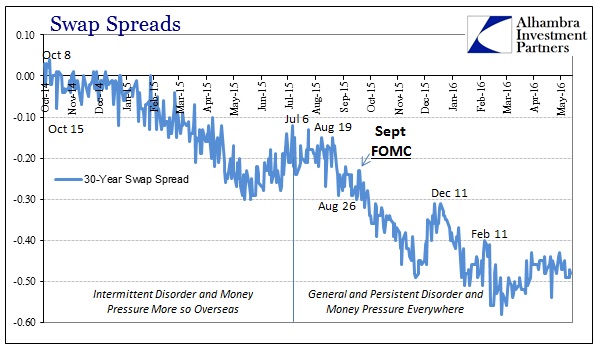

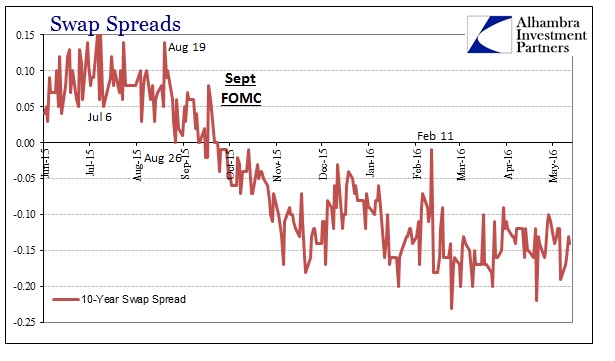

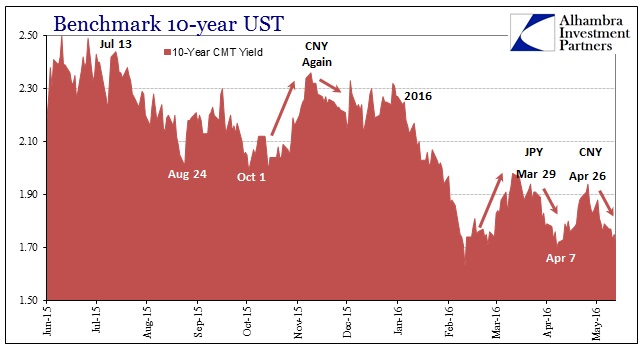

Is anything actually different? Obviously, the mainstream believes it but there is scant evidence beyond risk markets. Stock and junk bond prices rebounded almost exclusively without any confirmation or corroboration in credit and funding. Swap spreads and eurodollar futures barely budged while the S&P 500 briefly threatened a new high. The 10-year treasury yield is closer to a multi-year low right now than even a single further rate hike.

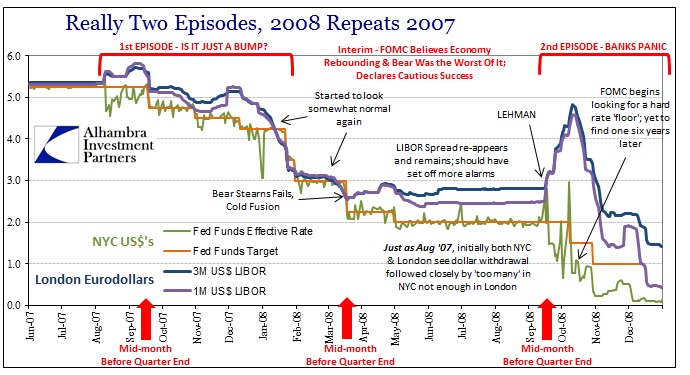

An unbiased read on the economic data shows some minor improvement but not nearly with enough emphasis or difference to suggest that the risks now are any different as when the year started. As my colleague Joe Calhoun and I were talking today, we even said the same thing at the same time, it is so very reminiscent of the period right after Bear Stearns in 2008. This is not to suggest the economy is nearly so bad now as then, only like then both markets and the global economy sustained a surprising (to the mainstream) and surprisingly heavy blow only to seemingly (on the surface) survive it with but minor damage. That led to an enormous outbreak of cautious optimism expressed no more clearly than by Ben Bernanke as late as June 2008:

"The risk that the economy has entered a substantial downturn appears to have diminished over the past month or so."

That view dominated the FOMC discussions of that time. Only a few weeks after Bernanke’s unleashed self-assurance, the Committee echoed almost exactly his remarks.

HOENIG More broadly, turning to the national economy, I have revised up my growth estimate for the first half of 2008, but it has made little change in my longer-run outlook. Compared with the Greenbook, I see somewhat stronger growth in the second half of this year and somewhat weaker growth next year and in 2010. I continue to judge that the potential spillover effects from the financial distress have understandably been overestimated in this Committee’s recent decisions and in Greenbook forecasts in recent months.

LACKER On the whole, I think the risk of the national economy sinking into a serious recession has receded, and the growth outlook has edged up a bit. I was relieved by the strength in retail sales in May as well as the upward revisions for April and March. The ISM indexes have steadied at right around 50 over the past four months; and although the labor market has been weak, it has not yet shown the accelerating declines that I feared.

Janet Yellen said, “the strong incoming data on spending eased my fears that we are in or are approaching a recession regime” before expressing confidence in rate hikes starting in December 2008!

The difficulties in understanding the non-linear nature of these economic events point to differences in types of economic events. Recessions, for example, were always a single event; a straight line down followed by a straight line up. Thus, if the contours of that “up” start to appear it is entirely reasonable to suggest that the trough has been reached and that it is only going to get better from there. Every post-war cycle followed that “V” so it was unsurprising for laypeople to expect similar conditions. Those that have given themselves the task of managing the monetary and economic affairs of the United States, however, should have made it their only business to know different.

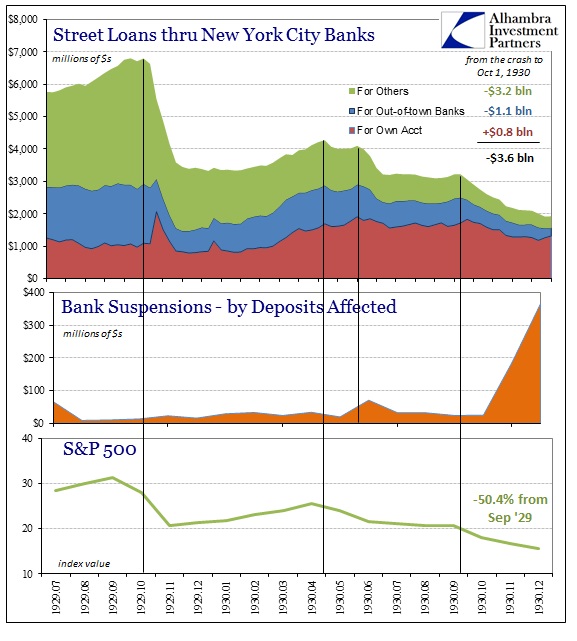

If we look back at the Great Depression, for instance, it followed a similar uneven path much like the Great Recession. It was a string of separate monetary problems that after each economists and business leaders were also convinced that the worst was over; only to find that a new low in the market or the economy was indeed quite possible. On September 19, 1930, for example, Arthur Lehman (of Lehman Brothers) was quoted as saying, “…improvement in business is slow but is nevertheless gaining; recent trends indicate no lines of business are getting worse, while a few are getting better.” Instead of recovery after the initial severe downturn, the first of the great waves of bank runs began only a few months after he expressed such guarded relief. He was far from alone, especially since it was difficult to even consider how an already bad depression by that point could yet become a Great one.

Economic events that have the heaviest financial and monetary components don’t seem to follow the same “rules” or patterns. That was certainly true of the Great Recession and panic, which were really two separate panics. The failure of Bear Stearns was likely the end of the first or close to it, but even afterward the system was beset by constant irregularity and dysfunction even though some conditions looked improved. Economists and policymakers chose to see that pause after the first wave as at least a good sign that it was all over because of their straight line expectations; from the FOMC perspective, they even declared it likely over because of their “heavy” intervention and “accommodations.” From their traditional view of the monetary system, no further systemic illiquidity could have been likely given so much “stimulus.” The evidence, however, was right in front them.

PLOSSER Given recent economic developments and the improvement in financial market functioning, coupled with our accommodative stance of policy, it seems pretty clear to me that, if the economy continues to evolve as it has over the past couple of months, we should move to raise the funds rate. This is also the view of market participants, whose expectations for policy have steepened considerably over the intermeeting period.

Though Philly Fed President Charles Plosser’s statement was made also at that June 2008 FOMC meeting, it sounds eerily familiar to every official statement being given now and for the past year or so during these “pauses.” Even his suggestion of “market participants” follows this current divergence, meaning that funding markets in 2008, as they are now, were not at all trading as if it were all over. He chose to find other “markets” less attuned to what were by then chronic “dollar” shortages in multiple formats (chart above).

After the oil crash in early 2015, it was declared “transitory” and even seemed that way from March to June last year. Then one wave of global liquidation hit, “unexpectedly”, which pushed the FOMC off its rate communication schedule, only for it announce a few months later that the worst was then over to where by December it could finally act. And then another liquidation wave crested and brought even more serious economic doubt, only to surrender yet again to resurgent optimism that that was the worst and the straight line points up once more.

While we can find several reasons to account for the “pause” in 2008 after Bear Stearns, in 2015/16 it seems far simpler:

The PBOC is “kind” enough to purchase these hiatuses at its own great cost, which is then turned into “the worst is over” by a mainstream still looking at everything as if it were still some variation of a “V.” A wider and fuller perspective instead reveals this halting, uneven but determined downward progression. Like the economic slowdown itself, it is one PBOC purchased step forward for two liquidation steps back. And it is the manner of that Chinese “purchase” that might be most relevant in the coming weeks and months (subscription required).

We live in an utterly complex world during an age of record complexity studying perhaps one of the most complex aspects of it all. Yet, there are times when it just might be that simple. The dominant correlation over the past year has been CNY against the world. The reasons for that are where intricacy and nuance take up, but in the most visible terms whenever CNY gets heading lower the world should duck…

Using our simple intuitive framework, to address the RMB illiquidity brought about by “selling dollars” and “buying yuan” the PBOC must reverse the process and start “selling yuan” and “buying dollars.” Just as “buying yuan” removes it from private circulation, so too would “buying dollars.” The result is greater CNY “devaluation” which really works out to a measure of “dollar” illiquidity (apologies for all the quotation marks).

But the PBOC has another problem – the ticking clock. Again, sticking with this simple convention, expiring or maturing forward operations dating back to early January require the PBOC to cover those past promises. Wholesale derivatives used in this manner are really just deferred funding commitments, meaning the PBOC must also “buy dollars” to fulfill the maturing leg of those forwards. Chinese liquidity ends up with the PBOC “buying dollars” to cover its internal imbalance of SHIBOR above 2% while also having to “buy more dollars” at the same time in the final act of its prior forward obligations. It is double intensity or worse depending upon the seriousness of especially that ticking clock.

The mainstream takes the absence of further liquidation as if there will be no more liquidations when in fact the likelihood of more of them only rises the more they are artificially “contained.” Though the exact details are different each time, it does seem to be the constant pattern of monetary-driven economic problems even looking back as far as the Great Depression. They don’t come in “V’s” as one singular downturn followed by equal recovery, they come in waves that rise in intensity after each one. In the early 1930’s, there were four of them: the great stock crash that drained the payment system of correspondent reserves followed by three successive and terrifying bank runs. In 2007-09, there were two distinct waves that were each quite powerful and disruptive. Since late 2014, there have been at least two so far, perhaps three if we count junk bonds/rubles/francs/oil starting in December 2014.

At some point, of course, there will be an actual bottom and one of these “waves” will be the last. For that to happen the fundamental condition would have to be seriously altered in an unquestionably favorable direction, not have been papered over by even the most seemingly adept central bank. Stocks after February 11 were suggesting at least the possibility, until CNY turned again, but funding never did.

The post Waves Not Solid Cycles – Echoes Of 2008 Warrant Worries appeared first on crude-oil.top.