Submitted by Charles Hugh-Smith of OfTwoMinds blog,

The institution offers facsimiles of recognition, but the individual remains powerless and interchangeable.

Most people working within dysfunctional institutions do their best to keep the institution operating, and they naturally resent their institution being labeled dysfunctional, as it calls into question the value of their work. Their role in the institution is the wellspring of their identity and self-worth, and attacks on the institution are easily personalized into attacks on their self-worth.

This is understandable, as the need to affirm the value of one’s work is core to being human.

Several factors work against the affirmation of an individual’s value in centralized institutions. While some institutions are better run than others, hierarchical institutions are ontologically in conflict with the human need for affirmation of one’s value, purpose and meaning.

While each individual seeks to be recognized as a valuable member of a productive community, the institution is designed to enforce obedience to the hierarchy and compliance with the many rules governing the institutional machinery.

To soften the enforcement of obedience, institutions offer various blandishments of recognition: employee of the month, etc. Hierarchical organizations that must compete for workers, such as technology firms, will actively court their employees with Friday parties and various bonding events to generate a sense of purpose and community.

But stripped of public-relations cheerleading, these ploys are deeply inauthentic. They aren’t designed to create a real community, but to simply soften the enforcement of obedience with superficial recognition of the human need for recognition and belonging. Their real purpose is to mask the employees’ powerlessness.

Why do individuals accept powerlessness? The institution offers them what is scarce: financial security and a position that offers an identity and sense of belonging.

But there is an intrinsic conflict between the institution’s need for obedience a nd the individual’s need for authentic community, purpose and identity.

Within small work groups, camaraderie between the employees nurtures authentic community. But this is not the result of the institution; rather, the bonding occurs despite the institution.

This conflict is deepened by the dysfunction that arises from the structure of all centralized hierarchies. In effect, institutions bribe individuals with the security of a wage and a position, but the individual can never be fulfilled by a bribe or a position that is intrinsically powerless.

Even those in positions of leadership are powerless to change the dysfunctions that arise from its structure. The ontology of hierarchical institutions is to restrict the power of any individual, as individual initiative poses a threat to the institution’s core dynamic, which is the commodification of all human labor within it.

People must be interchangeable within the institution for the hierarchy and rules to function. Every teacher can be replaced with another teacher, every administrator can be replaced with another administrator, and so on.

This ontological conflict between the individual and the institution is complex. The institution offers various facsimiles of recognition, but the individual remains powerless and interchangeable. The institution claims to be improving, but it remains dysfunctional and incapable of reforming itself.

The impossibility of meeting individuals’ needs for autonomy manifest in a number of ways; here are five examples.

The first is the individual’s powerlessness to change anything of consequence within the institution. Everyone knows it is dysfunctional, but even those in positions of nominal power are unable to effect any real change.

The second is the difficulty of feeling positive about one’s role in an institution that has clearly lost its way and squanders talent and capital as its default setting.

The third is the internal costs of complying with perverse incentives that strip away integrity, idealism and faith in the value of the institution’s output.

The fourth is the way in which rising costs and burdensome rules of compliance narrow the room to maneuver within the institution. There is little room for innovation or meaningful reform because the budget is devoted to maintaining the status quo, and compliance soaks up time, talent and capital.

The fifth is keeping up with the ever-shifting sands of political compliance, as metrics of productivity change with each administration. What was adequate before may no longer be good enough.

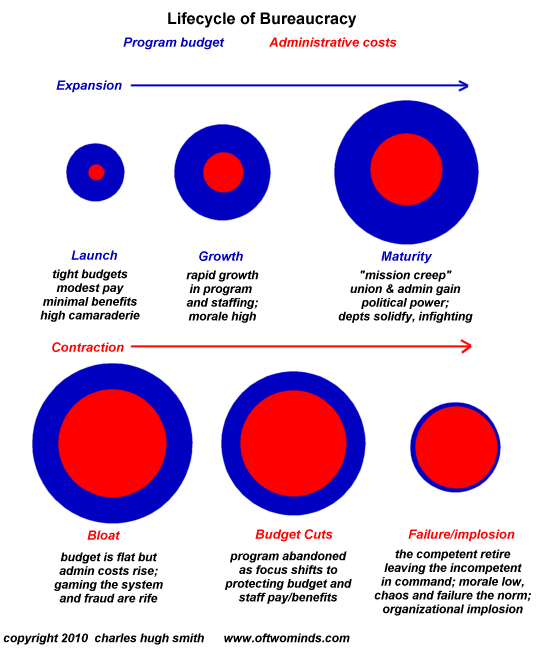

The institution is designed to enforce compliance of its employees as a means to fulfill its core purpose. But there are few effective mechanisms for transformation within centralized institutions; each additional rule of compliance is added to a pile that is rarely reduced. As the costs of compliance and legacy structures increase, innovation is crowded out.

Even worse, innovation inevitably threatens someone’s share of the budget and power pie, so any innovation immediately arouses powerful enemies within the institution.

As a result, the institution becomes increasingly sclerotic and self-protective, and the narrowing room to maneuver frustrates the most idealistic and talented, who either quit or are forced out as threats.

Those who choose to remain resign themselves to cynical conformity or they simply stop caring. Neither is conducive to valuing one’s work.

In other words, institutions self-select for those most adept at maintaining the illusions of productivity, empowerment, etc., while maintaining the structure that guarantees dysfunction and artifice.

I call this conflict between centralized, hierarchical institutions and human needs the crisis of the individual because the institution is unaffected by its failure to meet the human need for affirmation, autonomy and community; the only crisis that afflicts the institution is the loss of its funding.

The crisis of the individual is not limited to institutions. Indeed, it can even more acute outside institutions. Affirming one’s value and identity are difficult in an institutional setting, but they become nearly impossible for those who have no paid position in the workforce.

Like institutional dysfunction, the crisis of the individual is as unrecognized as the air we breathe. It is assumed to be not just the way the world works, but the only way it could possibly work.

But these pathologies are not gravity; they result from a specific arrangement of markets, central states/banks and the neoliberal imperative that maximizing private gain is the highest good.

This essay was drawn from my new book Why Our Status Quo Failed and Is Beyond Reform.

The post Why Nothing Progresses (Except Dissatisfaction): Institutionalized Powerlessness appeared first on crude-oil.top.